Warning: Programmer art ahead. Bar the orange backgrounds, made by Eric Grossman.

What we’re talking about

What we’re talking about

I swear it isn’t as scary as it sounds

There are two core words I’ll be throwing around throughout this post: Concept and Mantra.

Concepts are ideas; they’re seeds that steamroll into creation. Some of them sound genius and some sound pretty dumb. From there, some of the genius ideas don’t develop well and some of the dumb ideas wind up amazing. The truth is it’s hard to know the true value of a quick idea until you flesh out its potential.

A Mantra is a notion or description of the experience. It doesn’t necessarily describe the game you’re playing, or even any of its features or design. It’s the abstract description of the experience that you’re setting out to craft. It’s a description of the mood, tone, or core idea behind your game. Most (if not, all) great games have a strong mantra that is mirrored throughout the experience. This especially pertains to indie games, which are smaller in scope.

Designing backwards

Keeping mantra in mind, or finding one for the first time

Designing backwards is when you work backwards in the design process. In other words, taking a step back to re-evaluate the project. The goal is to either find a mantra for the first time or to qualify and evaluate the design decisions you’ve made thus far.

Here are the steps we took to find our mantra:

- Step back, be objective. Set aside favoritism.

- Summarize the project, break it into a list of features and details.

- Shrink the list as much as possible, leave only the one element if possible- the hook.

- Create a list of potential mantras for the remaining feature(s).

- Sit on it. Think of mantras (or your existent one), evaluate existent and potential features.

- Pick the mantra that best fuels the hook and juices the best part of the game.

- Reconsider or rewrite design documentation from scratch. Question everything using your mantra.

- Is the game better off with this change? If not, what did we lose, why is it worse off? Repeat if needed.

Sometimes this process changes the entire game, sometimes this causes slight modifications, sometimes it nullifies the entire project, and sometimes you just walk away with a mantra that makes zero changes. As a practice, I find it refreshing. Even if nothing changes, I qualify and justify the decisions I’ve made. It keeps my head straight and ensures that I’m on the right path.

I do this on a regular basis with long-running projects. On a monthly basis. My goal is never to destroy work I’ve done, but instead to question it and to qualify it. I ensure the work that I’ve done is coherent and contributes to the larger cause of the game. Designing backwards keeps your progress in-check and the big picture in mind.

Examples of mantras

Dark Souls

Learn through death and thrive on caution.

Journey

Encounter loneliness, camaraderie, and wonder as you set out on a journey.

Katamari Damacy

Novelty, ease of understanding, enjoyment, and humor.

InnerSpace (our game!)

A flying game that takes place in an inverted planet.

WOAH-HO, THAT’S NOT A MANTRA. THAT’S A CONCEPT!

Having a concept, but no mantra

This is a pitfall I used to fall in, often. I’d have a concept for a great plot, setting, or visual idea, but nothing to follow it up with. It’s a hole we found ourselves in, but we really loved the setting we had in mind. So we had to ask ourselves, “Where do we go from here?” The answer: Craft a mantra for the concept early in the process.

We knew we wanted to make InnerSpace. It was a great concept, but it felt unfocused. We set out to climb out of our hole that we’d dug; a hole of great ideas that provided a weak foundation for a game.

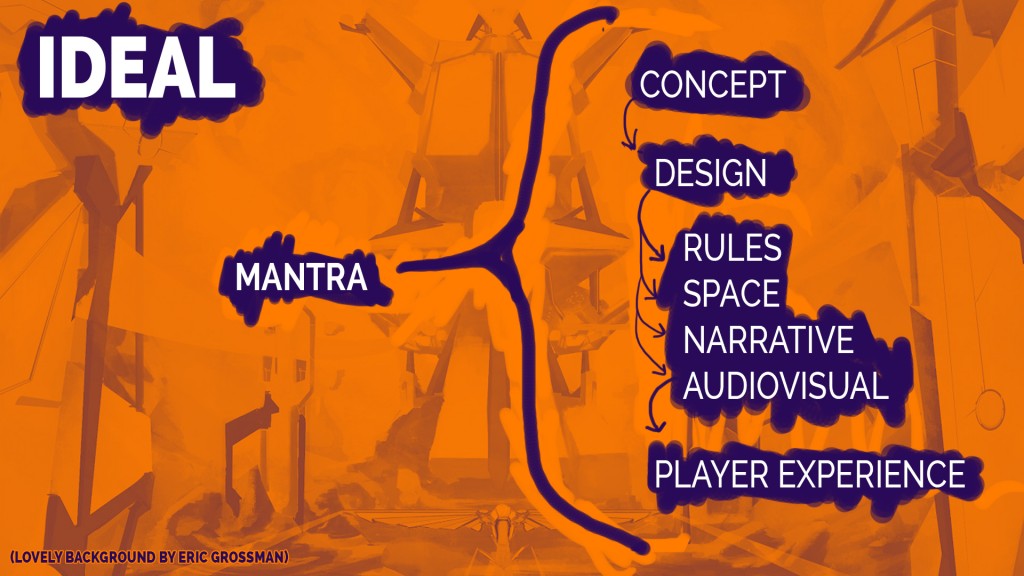

The ideal case

When things are just dandy

In an ideal world, we’d know the main objective of our game before even conceptualizing it. If we were capable of doing this, we would have had a mantra to abide by for our entire process. This makes design a lot easier, since it directs brainstorming very early on and keeps brains on-track. Games like Journey are born of this order, which creates an exceedingly coherent experience. A project we were involved with, Castor & Pollux,followed this work-flow, as well. Castor & Pollux began with a simple mantra: “Contrast,” which evolved into “Contrasting cooperative game-play,” after conceptualization. This made for a very coherent experience. All designed mechanics and visuals served this purpose.

Another big asset the ideal scenario brings to the table is clear vision. When managing a team, I’ve found miscommunication to be my largest enemy. Poorly communicated expectations or intent has led to a lot of wasted work. When our projects were well documented and the mantra was clear, all members operate for the same purpose. It doesn’t create a philosophical oligarchy, but helps direct creative minds, instead of controlling them.

The worst case

Throw caution to the wind.

This is when you either: 1. develop without mantra,or 2. fail to abide by your mantra.

In this scenario, cool ideas fire in all directions, and in the end, you wind up with a bunch of ideas that seem to lack that special something. It’s easy to wind up with mechanics, a narrative, and a visual style that all serve different types of experiences. Sometimes a few things would are coherent, but there’s always an outlier- that one component of the game that leaves it worse off.

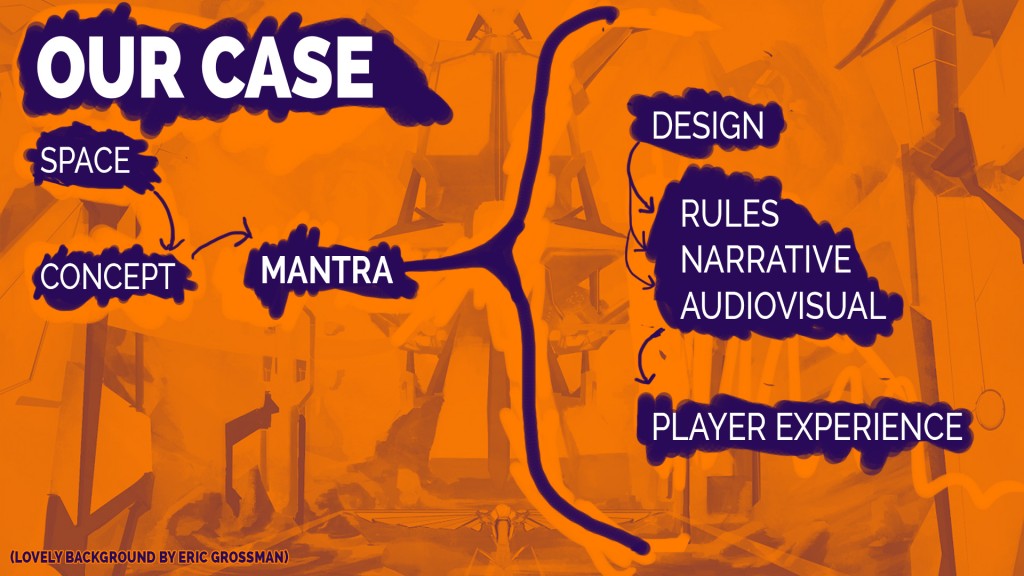

Our case

We happened upon something good, in the wrong order.

Often, a good concept comes in everyday life, or while day-dreaming. Starting with a mantra wasn’t possible, as we had already made progress, which meant we had to craft ours after the fact.

We thought of the setting first: an inverted sphere. This was our space, which then led to the concept that flying in this space would be fun. A flying game in an inverted planet. Two chunks of the pre-production process were already covered.

We took our long list of features/ideas and followed the steps listed above. Once we found our mantra, we then had to modify our space, question our concept, and even redo a fair amount of our design. This caused a little bit of conflict, since some of us liked designs we had to scratch. Is our game better off having reconsidered our mantra? Definitely. The game is more coherent, creativity in audiovisual and mechanic design is smoother, and we’re confident in the product we’re making.

Our concept:

A flying game that takes place in an inverted planet.

Our newfound mantra:

A live and interactive world to explore. A setting that induces curiosity and poses questions that can be answered.

Summary

TL;DR

When we found ourselves with a good concept and the beginning of a good design, we looked back. We considered the intent of the game and the experience we were setting out to craft: our mantra. Eventually, we settled on something fairly different from our current progress. We had to make a lot of changes and think really hard on the design to get rid of preconceived notions. We even lost a bit of work. In the end, though, we discovered a mantra that made for a better overall game that we’re proud to be developing.

Having a mantra before designing/conceptualization isn’t always possible, but work hard to get back to it.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks