The InnerSpace Style

My first experience of understanding what I didn’t want InnerSpace to sound like was when I was working on audio for the alpha build. I had already created three music tracks for the game and an aesthetic was set.

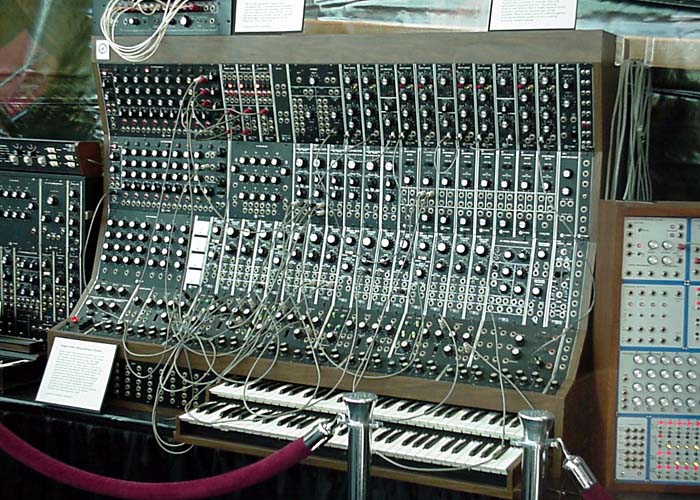

The in-game music, for the most part, was sustained and mellow. We made the conscious decision early (…early to the point where we only had concept art to use as reference) to stick to a very electronic sound palette, predominantly using different types of synths.

For a world that was so stylized, an orchestral score (or even any traditional instruments for that matter) seemed too realistic, while a chiptune style seemed, well, also inappropriate.

Before I explain further, check out this sample of one of the instruments used in-game for general aerial exploration of the hub world.

If you were to attempt to describe what sort of instrument this sounded like in one word, what would it be? Piano? Bell? Marimba?

It started off as a bell synth, but was given electric distortion, noise, as well as a myriad of ping pong delays and reverbs, so it could sound like something different. Something stylized. However, the sound still has recognizable qualities of traditional percussion instruments: the hit, the resonance, etc.

I became enamored with the hypothetical question, “If this instrument were to sound completely befitting of a game intended to have a realistic visual style, how would it change to match the stylized visual style of InnerSpace?

TL;DR: How can audio be stylized so it sounds like how you’d imagine it to sound, based on the visuals of the world?

Cohesiveness

For the InnerSpace alpha build, I attempted to make everything in the world sound realistic because, well, why not? If I were to do it that way, I’d at least have realistic mechanics to rely on. The water would sound like water, wind would sound like wind, the plane wing scraping against rock would sound like metal scraping against rock, etc.

However, as I progressed, completely realistic sounds appeared to be less and less appropriate. The visual style of the game felt too in tune with the “synthy” music that had been created. It felt like too big of a jump between music that was electronic and stylized, and sound effects/ambiance that felt entirely realistic. We realized that the sounds of the plane and the world would also have to share either musical qualities, or would have to sound like electronic renditions of realistic sounds.

Pushing the Boundaries

The downside of working on completely stylized audio is that everyone can look at the visuals and hear something completely different. I decided to start with the sounds of the individual feathers of the plane’s wings, since it was both a sound that the player would hear A LOT, and because it would help me to get a bearing on what the rest of the stylized plane sound effects would sound like.

Right away, I considered the way music elements were used as sound cues in Monument Valley and thought something of that nature might work well to add to the stylized nature of the game. (I’m referring specifically to the musical cues that play at around 5:40 when the platform moves.)

Working on a stylized sound from scratch is all about finding your boundaries. From working on audio for games, I’ve come to realize that a common director critique is that sounds can often be “too” something, whether it be “too metallic” or “too spooky,” etc. Generally, there are a set of boundaries that a sound should land between.

For me, the wing feather sound needed to be in the sweet spot between “too realistic/ metallic” and “too musical.” When I’d take a concept in for review and I’d hear it was “too” something, I could just dial back that element of the sound. From then on, finding not only the right sound, but the right balance of musical and realistic qualities, took trial and error, plus iteration.

The Process

The early versions of the sound are me attempting to find the boundaries that were “too musical” and “too realistic.” First, I tried feeding the original sounds from the alpha build into varying vocoders that essentially played the sounds’ waveforms into the main synths I used in the “Aerial Exploration” music track. I thought it would be a cool way to give the sounds a musical quality, while also staying true to the musical instrumentation. Also, instead of using realistic filtering when the environment changes (such as when the plane dives underwater), the sounds’ waveforms could just be fed into the synths used in the underwater track. That way, the music would serve a more impactful purpose in the world than to just be background music. However, that idea, in itself, was just too musical.

Next, I tried feeding the original sounds into varying vocoders but added noise and erosion, attempting to figure out a stylized sound that wasn’t that musical. Eventually, I made the second set of sounds, which ended up being too realistic.

So, with the boundaries of too musical and too realistic set, I was able to work my way to something more appropriate.

As you listen to the different versions, it’s rather easy to hear the wavering between realistic and musical. As I was mixing both realistic metallic sounds with musical bell hits (as you heard above), they started to get more of a “pluck” sound to them, which sounded too musical.

While the sounds contain elements that are realistic, they also contain pitched synth and bell tones. The question that we found ourselves asking was, “What should the pitches be, and how should they be dispersed among the wings?”

After some experimenting, we found that it worked best if seven notes of a scale were set, one for each feather, and that same scale was mirrored on the other wing as well.

So, I had the lowest note correspond with the longest wing towards the body of the plane. The realistic metallic sounds were also pitched accordingly with the musical notes, adding weight to the larger feathers, and lightness to the smaller ones.

After about 15 versions, the sounds above are the concepts that seemed to work best in both balancing between realistic and musical sounds, as well as pitch. However, since the musical qualities have such a strong impact on the mood of the game, the pitches of the wings can change.

For example, if the player is innocently exploring a world, the pitches of the wing feathers can reflect that sense of wonder with a “positive” sounding major musical scale. But, if danger approaches, then the scale of the wing feathers can change to something more minor, or even chromatic, to enhance the sense of uncertainty. This way of thinking can be applied to all of not only the plane sounds, but the environment sounds and ambiance as well.

This is one of then greatest and most fun perks of working on audio for a game with a very stylized visual look: the possibilities are truly endless.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks